The Moment of Moments

The setting couldn’t have been more vibrant. The Estadio Azteca was a cacophony of sound and colour. It was filled to capacity as 114,000 expectant souls were soaking in the atmosphere hours before kick-off. This was the tournament that gave to the world the now familiar Mexican wave, which at its inception had a true sense of a spontaneous, rhythmical and soulful charge, sadly no longer existing in those hackneyed adaptations to relieve the boredom of the bourgeoise. With the World Cup having to move away from Colombia due to the political unrest and the campaign of violence from the Medellin drug cartel, Mexico was chosen as a replacement despite the fact that much of its capital still lay in ruins following the 1985 earthquake. As members of his sporting team needed to carry out a last-minute search across Mexico City prior to this game to find a more suitable cloth for a replacement jersey to cope with the searing heat (the eventual option was chosen by their captain who commented “That’s a nice jersey. We’ll beat England in that”)[1], Diego Maradona led Argentina out onto the pitch against their bitter rivals. While the violence of the Falkland’s/Malvinas War was still fresh in the memory, for many Argentinians who also loathed the Galtieri regime, the robbery that took place during the 1966 World Cup was just as important. Then as now, the clubs met in a quarterfinals match. It ended 1-0 to the English after Geoff Hurst won the game with controversial goal (unlike in the final when the ball never crossed the line, on this occasion it was offside), but only after the inspirational Argentinian captain Antonio Rattin was dubiously sent after 35 minutes for apparently using “violence of the tongue” against a West German referee who admittedly spoke no Spanish. Playing at the same time at Hillsborough in Sheffield, the Uruguayans also had two players sent off in their match against West Germany by an English referee and were also eliminated in circumstances that were ripe for accusations of official match fixing[2]. The el robo del siglo (“the theft of the century” as the South Americans named it) is not something which many English like to talk about when reminiscing about their most glorious moment, while castigating the Argentinians as “cheats” for what was about to unfold.

It was a cagy first half in which the English strategy centred on stopping Maradona – which often translated into brutally kicking him as often as possible. Terry Fenwick might easily have been sent off on at least four separate occasions. But while Diego certainly knew how to fall with remarkable balletic fortitude, he never played the victim. Instead, what happened next was the greatest goal in the history of the game. It started with some trademark brilliance as the 25-year-old No.10 skipped past Glenn Hoddle and then managed to somehow pass the ball in between two more England players before delivering it out wide to the Argentinian forward Jorge Valdano. As the ball moved across Valdano’s foot, the cumbersome defender Steve Hodge sent it skywards into his own penalty area, where Maradona infamously rose and lifted the ball past the towering figure of Peter Shilton. While the English commentators debated whether it was off-side, as quick as the phantom punch that Ali landed on Sonny Liston a few decades prior, it was only when time itself was frozen that the truth about the most infamous goal in the history of the game became apparent. Or in the words of Diego, “un poco con la cabeza de Maradona y otro poco con la mano de Dios” (“a little with the head of Maradona and a little with the hand of God”). Seven minutes later, alongside the greatest of goals, the most widely celebrated in the history of the game also took place under the same Mexican skies. It was fittingly matched by the words of the Uruguayan commentator Victor Hugo Morales whose opening is still probably echoing across some celestial plane:

“Gooooooooooal! Gooooooooooal! I want to cry! Dear God! Long live football! Gooooooooooal! Diegoal! Maradona! It’s enough to make you cry, forgive me. Maradona, in an unforgettable run, in the play of all time. Cosmic kite! What planet are you from? Leaving in your wake so many Englishmen, so that the whole country is a clenched fist shouting for Argentina? Argentina 2, England 0. Diegoal, Diegoal, Diego Armando Maradona. Thank you, God, for football, for Maradona, for these tears, for this, Argentina 2, England 0.”[3]

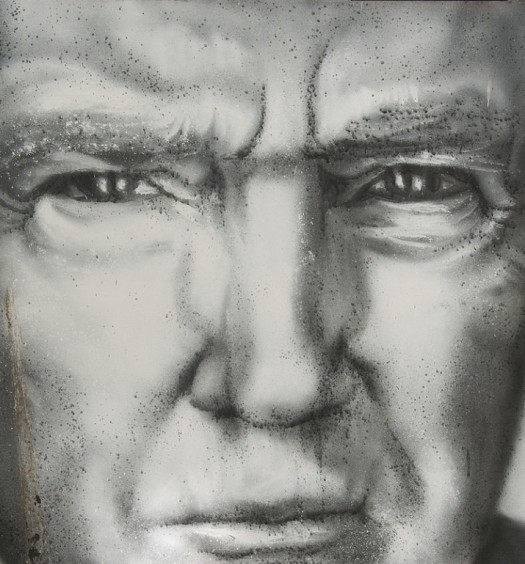

Simon Critchley has rightly argued that football is about “the moment of moments”[4]. Maradona’s Hand of God is “the moment of moments”. It is the most iconic image of the game. Nothing compares. If the game were to end tomorrow and it had to be reduced to a single image, this would be it. Yet despite all the global media in the stadium, only one photographer managed to capture with any clarity this momentous event, the Mexican photojournalist Alejandro Ojeda Carbajal. In Carbajal’s composition, Maradona is pictured in an eternally suspended present. An image that invites a different mediation on time. There is a perfect alignment at work as this diminutive figure elevates his torso, then some, to connect with the equally suspended ball. The keepers’ hands merely left to punch the air. While the bodies in this suspended duel focus the attentions, what matters in this frame is precisely the intensive quality of the air. Or to be more precise, there is something quite magical about the space, the air, the in-between player and the bone dry, arid barely playable grass. It is in this space where we imagine the electricity of the Azteca willing him ever upward. And it is in this space where we imagine the elevated man and the atmospheric fire beneath his feet. The angel who was also a devil, opening up a space that becomes a willing accomplice to the drama. An emptiness now filled with so much meaning it concentrates every known tension, contradiction and apprehension. This was phenomenological. A pure moment in which the world revealed itself to us as it was, though saying so much more than man, hand, ball, goal. An empty space, captured in this moment of moments shown as a truly poetic void. It is a barely considered absence, which despite all the futile attempts to give it some technical meaning by those armed with their statisticians measures and concerns with geometrical explanation, gives us the faintest of glimpses between the metaphysical and immortality. And Diego, in-between himself, his hand connected to the ball, but also as if connected to some heavenly string in a game being puppeteered by unknown forces that allows him to be majestically suspended between the fates of life and death. A man then suspended in time along a vertical axis that linked Olympus with Hades, somehow floating within a swirling vortex made possible by the rotational pull of the stadiums atmospheric charge, which now elevated him between the celestial stars and the daemonic possessions of the infernal depths. This is the in-between unnamed space of an act of creation. That wave meant something. And the suspension it generated from its magnetic pull testimony to the fact that humans cannot just live horizontally. They need to elevate. They need to embrace an aerial imagination in response to a world that was increasingly producing fleeting images. It is no coincide this goal occurred in 1986, the year when Fujifilm launched its Quicksnap 35mm model and the disposable camera became widely available on the market. Disposable cameras led to throwaway images. But Maradona’s dream of flight was anything but fleeting. A barely decipherable human star disbelievingly looked upon by a constellation of gazes. It touched deep into our psychological conditioning. And it even asks whether it is we who are the ones who were really suspended? Or to recall the words of Gaston Bachelard, ‘A breath of air is what turns the earth. An exquisite rotational movement is the dynamic imagination of this enormous globe of earth, as it is of every sphere’[5].

Finding Diego

In 2000, I visited Buenos Aires as a random tourist who was trying to still work out what I wanted from this life. This was a year before the great economic meltdown that would have such a devastating impact on the country and travelling to the other side of the planet for no apparent reason was one of the more random decisions I had made up to that point. I knew very little about Argentina, except of course Maradona. Looking back now, I can see how his presence was a strange companion on this bizarre adventure. Travelling with a friend at the time, there was no particular itinerary except to visit “La Bombonera”, the stadium of the notoriously passionate Boca Juniors, which is located in one of the most rundown and troubled barrios of the city. Having been the youngest player to debut in Argentina’s Primera Division, Diego signed for Boca in 1981 winning the league title in his maiden season. As I stood on the terraces of the then empty stadium, I could only imagine what it must have been like for both player and fans to witness the start of this timeless relationship, which would redefine the game and still gave the destitute reasons to hope.

Outside the stadium, I recall admiring the yellow and blue painted homes and a window display in one particularly small homestead that featured two equal sized and framed photographs: the Virgin Mary and Diego Maradona. I would later read about the Iglesia Maradoniana (the church of Maradona) which as an officially registered syncretic religion, featured its own version of the ten commandments that included how its followers should “Spread the news of Diego’s miracles throughout the universe”, along with the more basic demand to “name your first son Diego”[6]. Somewhat distracted looking at this display on empty and shadowed Argentinian street, out of nowhere a young boy who was barely 13 years old and wearing a fake Boca Juniors jersey rode up to us on a bike. He held out a broken bottle in his shaking left hand. I recall the glint of the sun on the shared ends of that green broken glass. I also recall his eyes pulsating with terror and desperation, high on drugs and low on life, which is so emblematic to youths in abandoned and violent places like these. I often think about the fate of that poor child, who risked his life for a few US dollars. I doubt he managed to live into early adulthood. A fate which would have probably been similarly repeated for the young boy from the muddied streets of Villa Fiorito had he not possessed the most remarkable abilities from such an early age.

A few days later we were invited by some locals we befriended to watch another local derby between River Plate and Independiente at the Estadio Monumental in a more salubrious part of Buenos Aires. I was particularly keen to see at the time Ariel Ortega, who born within a few days of me was the latest in a long line of speculated heirs to Maradona’s empty throne. I felt remarkably at ease, despite what had happened a few days prior. In fact, I felt remarkably privileged at the time, recalling the images of Mario Kempes and the tickertape flooded pitch during that victorious final held in the same venue back in 1978. Only later would I hear of the stadium’s darker history and its symbolic significance to the military dictatorship led by the right-wing General Jorge Rafaél Videla, which was arguably at its most oppressive, brutal and torturous in that very year[7]. As Will Hersey noted, ‘In earshot of the stadium drums, just a few streets away, inside the tree-lined campus of the Navy Petty-Officers School of Mechanics, the junta’s flagship torture centre continued to operate. The largest and most notorious of several hundred such concentration camps, this was one place where “Los Desaparecidos” were taken. The Disappeared. An evocative term more accurately describing the victims of state-sponsored murder. The junta wasn’t going to let the World Cup stop its work. In fact, quite the opposite’[8]. For this reason alone, the victory of 78 still haunts the Argentinian psyche, which makes the success of Maradona’s 86 team more than a continuation of success. Had Diego not been overlooked and have been selected in 78, might he have also succumbed to the subsequent association with the regime that has continued to burden the likes of Kempes? As a distanced warmup, Diego’s response would be to lead Argentina to the under 20s World Cup a year later. We cannot know for certain if this might have changed anything. What we can say is 86 would become a form of internal psychic healing for a people whose collective anger and shame found a way to overcome the demons of the past through their collective footballing spirit. Or to paraphrase Frantz Fanon, “the colonised man found his freedom in and through football”[9].

Later in the evening one of our hosts took us to the renowned Buenos Aires nightclub Pacha, which was situated not too far from the Monumental, where he worked as one of its main promoters. He recalled a story from one evening around the millennial celebrations when it became apparent that Maradona was actually in the club. As the DJ was about to finish his music set for the evening, Diego could be seen on a podium shouting for one more song. The DJ dutifully obliged. Whether this was real or just folklore really didn’t seem to matter. Everybody here seemed to have their own personal story of Diego. Deploying my own creative licence, I only wished that the song on that occasion playing out was the Argentinian singer Rodrigo’s La Mano de Dios[10]. Like I pictured him walking out onto the pitch at la bombonera, so I now imagined him there, but working in an opposite flow to the crowds. As they jumped in the air, over and over, recreating their own flight with left hands raised in unison bellowing out the words to Rodrigo’s intensive anthem, so I could picture on the packed dancefloor the ghost of Maradona, seamlessly gliding past the fellow revellers as effortlessly as he did with the English in the Azteca. There is an important point to make here that takes us back to the ancestral heat of Mexico in 86. The Hand of God is perfect in the act of its very suspension. You don’t need to see the build-up or even know it eventually found the back of the net. The goal of the century in contrast is all about movement. A single frame can never do it justice. If the former then is power to the testimony of photography, the latter would be testimony to the power of the moving image. It was truly cinematic. But more than this, due to limits of camera technology at the time (overcoming motion distortion was only just introduced into this tournament for single shot cameras, which again added to the Hand of God composition) as each freeze frame carries over blurred traces from the previous sequence, so the movement is defining. It is a mistake however to reduce this to merely a goal. The ball going over the line is the least interesting part of the entire legendary sequence. Or it is merely a confirmation, like the goal itself was a confirmation to prove that what happened a few minutes earlier didn’t really matter because Diego was also capable of doing this. Diego didn’t score just a goal in the 55th minute. He performed the most eloquent ghost dance.

Children and adults, the world over would recreate the dance of Maradona, often just with some imaginary ball. Somebody once posted a video onto youtube which featured an edited version of the “goal of the century” with the ball erased. That was a stroke of genius that really captured its essence. In that moment, Diego made the ball irrelevant. Very few have been able to do this, let alone on the biggest stage. While it is tempting here to repeat the words of the BBC correspondent Byron Butler who resigned himself to note how the English defence was simply “left for dead”[11], if an exorcism needed to take place, it was for a man who was always ghosting through. And looking back, I now see that in Buenos Aires you are always in the presence of Diego.

It was my final day in Argentina, and I wanted to take in the city for one last time. I left the hotel that was close to Plaza de Congreso on the Avienda de Mayo in the Monserrat area of the city. I took an early morning walk up to the intersection with Av. 9 de Julio and looked left and gaze once again upon the Obelisco de Buenos Aires that was faintly visible in the far distance. I first recalled seeing this imposing imperial structure on television as scenes of Argentinian celebrations were beamed around the world in 86. Walking straight ahead, I continued onto the Casa Rosada, which remains so symbolic in concentrating the hopes and terrors, the passion and the tragedy of this Nation. It would later be the site where Maradona’s body would lie in state. While his body was granted all the honours usually reserved for a beloved fallen President, outside there would be contrasting scenes, from the wailing sounds of the weeping chorus, the loving embraces between rival fans, along with subsequent violent clashes between the people and the police. Chaos reigned as the pageantry commenced. Even in death, it seemed, Maradona was capable of sparking the social flames that dance with all their complexities, contradictions and uncontrollable passions. On this morning, I noticed a group of elderly women protesting at la Plaza de Mayo. I would later learn much more about their continued fight for justice and attempts to recover the bodies of the those taken during the junta. Formed in 1977, they would also be caught up in the violence that was part of the leftist clean-up, and which accelerated during the build-up to the 78 World Cup. In the words of Taty Almeida one of the Mothers of the Plaza “When you hear the word ‘World Cup,’ it reminds you … of the disappeared, of the kidnappings, of the murders.” One of those murders included a prominent founder of the mothers, Azucena Villaflor. Having taken out an advertisement in a local newspaper publishing the names of the missing children on Human Rights Day in 1977, that same evening she was kidnapped and taken to the Navy Petty-Officers School of Mechanics. Villaflor’s remains would be identified in 2005[12], buried in an unmarked grave. She had been killed having been thrown out of a helicopter in one of the notorious death flights (vuelos de la muerte), her body subsequently washing up on the shores of the River Plata[13]. The organisation responsible for locating her body, Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense (EAAF), was also known for having found and identified the body of the Argentinian Ernesto “Che” Guevarra in Bolivia, whose iconic image was tattooed on Diego’s right arm. In 2010, Maradona personally led a campaign calling for the Nobel Peace Prize to be awarded to the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo for their dignity and fight, and to remember the estimated 33,000 people forcefully disappeared during the Dirty War in Argentina between 1976 and 1983.

My return walk took me back past towards the Congress building, which sits in almost perfect alignment across from the Casa Rosada and halfway intersected by 9 de Julio. I decided to sit and drink a final coffee in a moment of solitude in this beautiful city. It was another golden morning. While the day was only a few hours old, already there was a photogenic young couple practising tango beside the fountains. Only in Argentina, I thought. I noticed a homeless vagabond sat close by who was unshaved and dishevelled; yet still had a welcoming demeanour. His right leg was amputated. As I walked past, the vagabond shouted out in English “hey, senor, where are you from”? Despite two weeks in the Argentinian sun, it seemed I still couldn’t hide my northern hemispheric complexion. I responded that I was from the U.K. He just gave a wry smile, and without saying anything further simply gestured like he was scoring a goal with his left hand raised above his head. We both laughed and I left, knowing what he meant. I later found out from the hotel receptionist the plaza was a place where a few former soldiers who were injured during the Falklands/Malvinas conflict used to congregate. Like so many traumatised veterans the world over, he was cast out and now lived on the streets, discarded by State, which only really needed him for his violence. There seemed to be such a tragic symmetry to these lines now divided as neatly as any football pitch, where on one side were families searching for the disappeared and on the other those who, in the end, prove to be just as disposable as anyone else. It seems that somethings in life are more important than war and politics, identities and petty victories, divisions and tribalism’s after-all.

I Have a Theory about Maradona

There are many ways we might offer a general theory about football, which in turn offers a concentrated insight into life itself. Football has never been just a past-time. “It’s more important”, the late Bill Shankly once observed, “than life or death”. Recognising then that football is more than a competitive distraction from important worldly concerns, what happens in the game provides a telling window into the world we inhabit. Like other sports with global appeal (though I can think of none which come close in this regard), to echo the mantra of FC Barcelona with whom Diego had a short-lived relationship, it always has been “more than a game”. Already recognised as the best player on the planet, Maradona signed for the most romantic club on the planet for then a world record transfer fee of around 5 million from his native Boca Juniors. He agreed to join them after his first World Cup, which was held in Spain in 1982. Argentina would be eliminated in the second round, with Maradona subjected in a match against Italy to one of the most brutal assaults ever witnessed on a football pitch at the hands of Claudio Gentile. That was one way to stop the genius. The alternative was captured by the photographer Steve Powell in the match against Belgium[14]. If you were going to contain Maradona, his picture tells in the most resolute and unexaggerated of ways, you are going to need half the team. But this was the World Cup in which El Diego also become El Diablo in the eyes of some, ironically in the stadium of the club he was about to join following his dismissal for a violent retaliation in their elimination match against Brazil. After a short and tumultuous period playing for the blugrana, which ended in another dismissal for violent conduct after the Copa del Rey final – a game again in which he was subject to particularly aggressive treatment, Maradona left for Naples in another world record transfer. The rest as they say is history. But as if the Gods were somehow conspiring or at least writing the script, the allegiances he further dynamized would later be pushed to the limits when Maradona scored a penalty that sent Italy crashing out of the 1990 World Cup in a match held in Naples. A match in which he asked the locals to support Argentina, knowing full well the divisive nature of Italian politics.

Mindful of the way football invites political comparisons, grand theorists of the game might invariably turn here to the ruminations of George Orwell, who insisted the game was effectively a “war without the bullets”. And that international football especially was “a continuation of war by other means”. This might invariably have political theorists and other strategists debating about the relevance of Carl Schmitt’s ideas, which argued that the essence of politics was defined by clear lines of enmity. The politics of life thus so determined between friends and enemies. Maradona embodied such rivalry more than any other player. On numerous occasions he became a national pariah and the prime focus for revolutionary affection and colonial consternation. But Maradona could never be neatly defined within such crude identity-based categorisations, so seductive to modern ways of seeing politics and the world. He would exceed the entrapments of such dialectics, where even in 86 the English had to simply look on and appreciate the sublime wonderment of a player who was as otherworldly as the shadow cast on the pitch of the Azteca, which reminded us of some mystical ancestral past. Maradona didn’t just belong. He often belonged in ways that exceeded the boundaries of worldly construction, dancing with different spirits who refused to be contained and neatly colour-coded, however captivating that Argentinean blue. I am also reminded of the insightful words of Simon Critchley here, who notes: “I have spent my entire academic career listening to people give papers, thousands of them. On no occasion that I can recall did the response to a speaker take the following form: ‘Dr. Smith, thank you for your completely convincing talk. You were right. I was wrong’. It never happens. Yet, in relation to the unserious stupidity of football, it happens a lot. Peculiar, no?”[15]. Even the English who continue to despise him, still concede about that second goal.

Social scientists (especially those of a more Marxist persuasion) might turn instead to the well documented inequalities the game makes most apparent[16]. Certainly, as in life, football has been subjected to intense corporatisation and the effective commodification and technologization of everything. Indeed, while at a young age you probably first encounter the reality of economic inequality directly through football boot envy, later you see how the entire game, its rules and regulations, tend to favour the already successful, wealthy and dominant in the game. This wasn’t lost on Maradona, the man who was often in the company of Fidel Castro (who he referred to as his “second father”) and who in 2007 declared himself a “Chavista” while explaining: “I hate everything that comes from the United States. I hate it with all my strength”[17]. This would be tied to his concerns with US imperialism, notably evident in his vocal support for the anti-war movement against the invasion of Iraq[18]. Maradona would also later develop a friendship with the now ousted Evo Morales of Bolivia, campaigning against the perceived FIFA injustice to prevent games from being played at high altitudes, which tended to favour the Bolivians. Some inequalities did matter Maradona understood, especially if they favour the poor. There is no denying then the wider revolutionary appeal of Maradona. The boy from one of the poorest barrios in Buenos Aires, who would wear the colours of Boca to rally against the economic privileges of those who supported River Plate, who would take the fight against the colonial powers of Spain and England, while having River’s fans passionately chanting his name as if he was one of theirs, who would wear the colours of the Neapolitans to fight against the long established prejudices of the Milanese, who would decry at every possible opportunity the now proven nepotism and corruption that governed FIFA, while appealing against the wider corruptions apparent in all quarters of society, from the Catholic Church to the forces of global oppression.

But what made Maradona a real revolutionary wasn’t simply some fight for orthodox political and economic justice (which no doubt puts him in marked contrast to the silences of Pele). Nor of course should we look upon Maradona and seek to impose some kind of socialist puritanism. What Maradona does after-all show in abundance is how the only thing that’s equalitarian in the game is the perfectly round ball that unites complete strangers. Everything else is measured by its inequalities and differences. More than this, Maradona was totally unique and radically singular. Not only does this encourage us to confront deeper and more timeless questions about the human condition, but it also makes him far more revolutionary than anyone who would simply box him into concerns with the wealth of nations or the predictable conformist demands of the identity politics police. Invariably, when trying to answer such questions, we might consider how Maradona’s personal life reveals what students of ancient philosophy might call tragedy. One only need to view Asif Kapadia’s considered and non-judgmental film Diego Maradona (2019), to note how its plot of heroism, villainy, betrayal, revenge, violence, sexual misadventures, organised crime, state persecution, intoxication and a sense of a tragic foreboding might easily have been written by Sophocles. And there is no doubt that football stadia have become theatres also defined by fate, where truly as Shakespeare observed all the world was a stage. While it is enriching to see Maradona as Dionisius with a ball, raging against the Apollonian forces that govern from up on high, even here there are answers that even Nietzsche (the most famous student of tragedy and advocate of the Dionysian spirit) might have found hard to reconcile. Maradona demands more if we are to consider what his memory now brings to any concern with developing the theory of the game, which is also inseparable from theories on life. I would now turn to the opening line from Eduardo Galeano’s Football in Sun and Shadow, which gestures to a more poetic understanding:

The history of football is a sad voyage from beauty to duty. When the sport became an industry, the beauty that blossoms from the joy of play got torn out by its very roots. In this fin de siècle world, professional soccer condemns all that is useless, and useless means not profitable. Nobody earns a thing from that crazy feeling that for a moment turns a man into a child playing with a balloon like a cat with a ball of yarn, a ballet dancer who romps with a ball as light as a balloon or a ball of yarn, playing without even knowing he’s playing, with no purpose or clock or referee.

Play has become spectacle, with few protagonists and many spectators, football for watching. And that spectacle has become one of the most profitable businesses in the world, organised not for play but rather to impede it. The technocracy of professional sport has managed to impose a football of lightning speed and brute strength, a football that negates joy, kills fantasy and outlaws daring.

Luckily, on the field you can still see, even if only once in a long while, some insolent rascal who sets aside the script and commits the blunder of dribbling past the entire opposing side, the referee, and the crowd in the stands, all for the carnal delight of embracing the forbidden adventure of freedom[19].

Nobody carried the spirit of the insolent rascal better than Maradona. What Maradona showed to us most fully is that football, while often tragic and full of disappointment, can reveal to us a beautiful chaos – a landscape populated by angelic demons. But this is not a question of religiosity, even though the ball can often appear like a sacred object, the stadium the cathedrals of our times, and the game as devout as any religion followed by so many. What keeps us enthralled, what Diego embodied, is a theory of football that marks out the exceptional from the normal. Maradona was the exception. He stood against the norm – the norms of expectation, the norms of the play, the norms of the spectacle, the norms of the rules, the norms of life. The normative is tedious, he knew. It offered nothing new. It is bound up with petty regulations and legalities. It is policed, appropriated, fixed into place and overlaid with righteous moral indignation. The normal is the routine, the technical, the followers of the lines, the statisticians of good measure, the engineers of biological conditioning, the princes of received privileged wisdom. That doesn’t mean to say it cannot be good; often in fact the normal is very good. It is well behaved, performing as expected, living up to expectations, turning creativity into repetitive wonderment as the predictable play of life is bound up with equally tedious narratives of human progress. Maradona progressed nothing and nothing he did can be repeated. You may make false approximations, but the story is his alone. Bruce Lee once remarked that the real sign of greatness is that a person doesn’t remind you of anyone else; that there is no comparison to really be made. Maradona is the incomparable. And this brings us closer to a theory of the exception. The exception is exceptional. It is transgressive. It knows the rules, appreciates deeper the intimacy of the lines, but only to see how they are constructs of mediocre technical minds. The exception is the uncontrollable excess. It refuses to be pinned to a board. It has no time for the civil or the domestic. It is the outrageous. The unpredictable. It is the contradiction that refuses to be drawn into the greyness of existence. The exception is the original. It is the timeless beauty. The lightening of all possible storms. A power of spontaneous invention. Maradona the exception, football the rule.

Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina

The sadness was unbearable. The diminutive player looked on as Germany were crowned world champions. Yet another victory for the European powers of the game. He was in the eyes of many the greatest player to ever play the game. Unrivalled in terms of his all-round contribution. But this was his moment. He knew it. And it had passed. The unplayable was reduced to a mere statute of the man he always was. Lionel Messi’s dream of lifting the golden trophy was watched by millions. It seemed the shadow of Maradona, who previously managed the mercurial Argentinian, would continue to cast over the expectations of the Nation. Messi would remain the greatest player. But Maradona would remain the greatest. That’s the difference.

Unlike Diego in 86, Messi had so many routing for him and watching with sure anticipation. Maradona was brilliant, but he never carried the hopes and expectations of the entire footballing world. Most actually wanted him to fail. He belonged to the underdogs. He wasn’t expected to reach the top of the mountain, but he did all the same. There was a sure defiance to his journey, which truly set him apart. Messi would cut a lonely figure, inconsolable, crying the tears of a man who couldn’t compete with his own standards. The tears Maradona cried on Italian soil in 1990 having also lost to Germany were not the tears of a man, they were the tears of Eros. They showed that football truly was more than a game, it was life, as it appeared in all its tragic and chaotic beauty.

Timing is everything in football. Timing is also everything in death. Some players play for too long. Not knowing when the time is right to leave the stadium for the last time. Some people have also lived for too long. Not knowing when to leave the worldly stage. That Maradona departed in 2020 seems perfectly fitting. The game had already been under threat in terms of its poetic appeal for quite some time. Certainly, through the mid 90’s and into the new millennium, the neo-liberalisation and financialization of the game has created a situation where the spectacle of winning had become everything Galeano feared. We would see this embodied in the likes of Jose Mourinho, whose total commitment to the technical over the poetic resulted in strategies where the only ambition was to make it anything but football: – a technical form of playing without playing. Sure, there would still be breakthrough moments, such as Pep Guardiola’s FC Barcelona, who properly carrying out to its full potential the artistic vision of Johan Cruyff reminded us just how beautiful the poetic side remained. And yet for the past 5 years, the acceleration in the technologization of the game was more than threatening to truly kill its poetic spirit, which was borne of passion, errors and mistakes, the spontaneous, the unexpected, the untimely, the controversial, the outrageous. This enframing of the game through “advanced” technology, as Martin Heidegger might have suggested, wasn’t about making the game more transparent. It would suck the life out its one defining element: the human.

Had the various technologies which have been threatening to destroy the game for a number of years been around in 86, there would have been no Hand of God. And as such, the world of football would have been deprived of its most iconic moment of moments. Just because it represents a transgression of the rules, doesn’t always make it cheating or bad. The beautiful chaos of the game should always remain in excess of the laws that govern it. But 2020 also reminded us of another important factor to the game’s human side. Playing in empty stadiums is like playing in a mortuary policed by the suited walking dead FIFA bureaucrats or technocrats of any persuasion. Without the passion of the crowd, the game is meaningless. Football at its best, remains an artform that reveals through its own language a certain poetry in motion, which defines any technical description and all their data-setting et ceteras, et ceteras. This is perhaps what Bill Shankly had in mind when he called it “working-class ballet”. All the facts, statistics, numerical analysis, percentage rates, tell us nothing about how a person, a crowd, a nation, a romantic feel when the final whistle blows. They tell us nothing about how a player can be silent for 80 minutes, then in a moment of brilliance change the outcome by virtue of their unique presence. And they certainly cannot come close to explaining the life of someone like Maradona, who was just as passionate and unpredictable when watching from the stands as he was on the field. The passion of Maradona then was not a tragedy, but a life complete. We can only imagine how he might have rejoiced seeing Messi finally lead Argentina to glory at the Copa America 2021 in the Brazilian Maracanã of all haunting places.

‘Life in the end’, Jacques Derrida once mused, ‘will have been so short’. And so, it proved to be. In the biblical story of the passion, the ghost of the saviour appeared after the resurrection. But maybe with Diego it was the reverse. From time to time, we encounter exceptional people who literally appear larger than life. But what does this actually mean? Like Muhammad Ali before him, maybe Maradona was always an apparition. A player who gracefully went past players with consummate ease, not because he simply left them for dead as he ghosted by their immobile bodies, but because he always was a ghost walking amongst us. The wonder of Maradona’s most iconic moments is that they occurred in an age before the advent of digital technologies. The game was imperfect, it was analogue, and it was never fully decipherable. Even the most advanced freeze-framed stills still leave gaps and traces of his movements. We are denied the ability to zoom in and gaze upon which finger truly elevated the ball up to the celestial plane where barely visible dancing stars reside. This is the world as image when it was able to retain something of the mystery. Regardless of how many reruns we demand from either of those England goals, we can never quite fully grasp what really happened in those moments. Sometimes we lose something magical, when we gain too much knowledge or can unnecessarily map things from every conceivable angle. Perhaps it’s for this reason why Maradona continues to haunt us with the ancestral fires of a beautiful chaos, which the game can only now look back upon with a melancholic lament. If there is a tragedy to write of then, it was not the trials and tribulations of Diego Armando Maradona. Looking back at us, what his existence shows is how the real tragedy is what has become of the game, what has become of us. Then again, maybe we shouldn’t cry or mourn for a phenomenon who was always greater than his brief mortal adventure on this pitch of life. No tears should after-all fall in the presence of an eternal apparition.

Notes:

[1] See https://www.fifa.com/worldcup/news/curious-tales-of-world-cup-shirts-2340153

[2] The English authorities in fact went to considerable lengths to disadvantage and disrupt the preparations of all non-European competitors. On this see Simon Burnton, “Why not everyone remembers the 1966 World Cup as fondly as England” (The Guardian, July 24th 2016) Online at: https://www.theguardian.com/football/blog/2016/jul/24/1966-world-cup-final-conspiracy-refereeing-50-years

[3] Translation taken from https://www.whatahowler.com/how-the-world-heard-the-greatest-goal-ever-scored/

[4] Simon Critchley, What we Think About When we Think About Football (London, Profile Books: 2017) p. 27

[5] Gaston Bachelard, Air & Dreams: An Essay on the Imagination of Movement (Dallas, the Dallas Institute Publications: 1988) p. 47

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/football/2008/nov/12/diego-maradona-argentina

[7] For a harrowing set of testimonies on the violence in Argentina during the world cup of 1978 see Wright Thompson, “When the World Watched” (Esquire, 9th June 2014) Online at: http://www.espn.com/espn/feature/story/_/id/11036214/while-world-watched-world-cup-brings-back-memories-argentina-dirty-war

[8] Will Hersey, “Remembering Argentina 1978: The Dirtiest World Cup Of All Time” (Esquire 14th June 2018). Online at: https://www.esquire.com/uk/culture/a21454856/argentina-1978-world-cup/

[9] Paraphrased from his Wretched of the Earth, Fanon invariably used the word “violence” in this context.

[10] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EAk-l1VHzBw

[11] As Butler reluctantly described in his live commentary for the BBC at the time: ‘Maradona, turns like a little eel, he comes away from trouble, little squab man, comes inside Butcher and leaves him for dead, outside Fenwick and leaves him for dead, and puts the ball away… and that is why Maradona is the greatest player in the world…he buried the English defence, he picked up that ball 40 yards out, first he left one man for dead, then we went past Sansom, it’s a goal of great quality by a player of the greatest quality. It’s England 0, Argentina 2: the first goal should never have been allowed, but Maradona has put a seal on his greatness. He’s left his footprint on this World Cup. He scored a goal that England just couldn’t cope with, they couldn’t face up to, it was beyond their ability… it’s England 0, Diego Maradona 2’. Cited at: https://www.whatahowler.com/how-the-world-heard-the-greatest-goal-ever-scored/

[12] http://www.ipsnews.net/2005/07/argentina-remains-of-mothers-of-plaza-de-mayo-identified/

[13] It is speculated that the washing up of her body was due to a miscalculation as the regime preferred for the oceans to leave no trace of the abducted. On this see https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2006-mar-24-fg-dirtywar24-story.html

[14] See https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/diego-maradona-of-argentina-is-confronted-by-a-posse-of-news-photo/1619809

[15] Critchley, What we think about when we think about football, p. 105

[16] Certainly, one of the better authors here is David Goldblatt, notably his book The Ball is Round: A Global History of Football (Penguin, London: 2007)

[17] Cited at https://www.insider.com/here-are-the-major-political-causes-diego-maradona-supported-2020-11

[18] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2005/nov/05/usa.argentina

[19] Eduardo Galeano, Football in Sun and Shadow (London, Penguin: 1997) P. 2